Work > Painting Archive

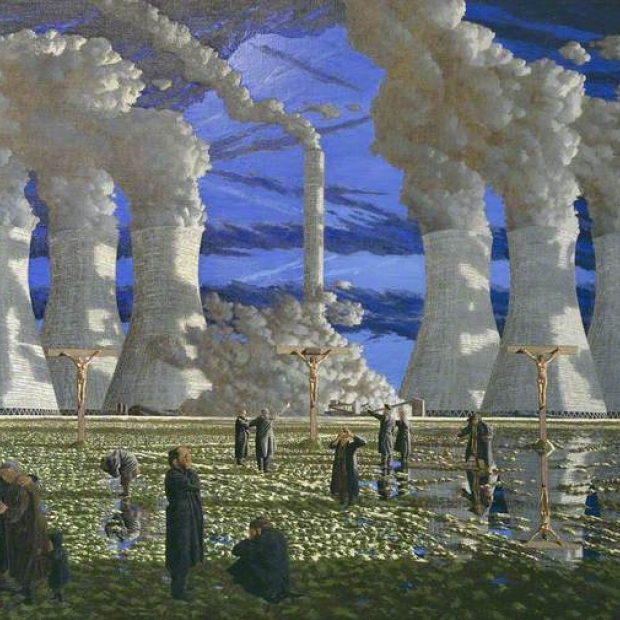

Menorah 1993

Oil on Canvas 157.4x195.9cm

The Ashmolean

The Menorah is the seven branched candlestick with cups made like almond-blossoms... the whole of it one beaten work of pure gold, which in the Book of Exodus Moses is instructed to place in the Tabernacle in front of the Holy of Holies: the place where God's presence dwells with his people. The Menorah thus becomes a kind of visible symbol of God's invisible presence. When the Temple in Jerusalem was finally destroyed the Menorah was among the treasures carted off to Rome, and a depiction of it can be seen among the reliefs on the arch of Titus. Throughout the Bible though the Menorah also appears in prophetic dreams and visions, and its last mention, in the New Testament, comes in the Book of Revelation where Jesus is seen walking in the midst of the seven candlesticks his hair white as wool, white as snow, and his eyes as a flame of fire.

When I first saw Didcot power station through the window of a train from Oxford to Paddington, the smoke belching from the central chimney reminded me more of a crematorium than a symbol of God's presence. And yet having said that, the astonishing sky behind the towers looked like the arch of some great cathedral, while something in the scale of the cooling towers themselves, with the light moving across them and the steam slowly, elegiacally, drifting away, created the impression that they were somehow the backdrop of a great religious drama. Both these ideas remained in my mind for many years, and developed in a series of paintings and sketches. On the one hand the crematorium-like chimney and the inhuman scale of the buildings brought associations with the industrial genocide of the twentieth century and the blank inhumanity of so much in human existence while on the other hand within the strange beauty of the scene was the insistent sense of some great redemptive moment. It wasn't until I realised at the towers, from the angle I had seen them, had lined up to form the shape of the Menorah, that I realised how these two impressions could be united, and realised that the drama to which they were the backdrop must be the drama of the crucifixion. In no other religious event is the absence of God so closely linked with his presence, or the tragedy of human life so intimately linked with its redemption. The extraordinary Jewish prophecies which see in the mysterious servant of the Lord, a figure apparently 'smitten by God and afflicted' but in reality 'pierced for our transgressions', say of him 'surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows'. Likewise the disciples of Jesus who see the crucifixion as the fulfillment of these prophecies, describe him both as a man crying out 'my God, my God, why have you forsaken me?', and as one who, even before his birth was named by the angel as 'Immanuel, that is 'God with us' '.